Uncertainty, CRM and Airplane Crashes

by Capt. Wong Wei Corgen

Imagine Felix Acero, a long-term expatriate businessman sitting in First Class on a comfortable, glassy-smooth flight on a Singapore Air Lines A-380. Felix is nestled in a kind of deep sofa, just two abreast, with plenty of legroom and charming service; it is only natural that he would strike up a conversation with the well-dressed gentleman sitting beside him.

Felix: “Are you enjoying the flight?”

“Well I’m a commercial jet pilot so I can never enjoy it the same way a passenger does.”

You both laugh.

“Rob Ashby.” They shake hands.

“Felix Acero. Glad to meet you. I’m Colombian but I live in Asia.”

Rob: “When I’m sitting back in the cabin as a passenger I’m always a little uneasy – continually listening to the engines, feeling any movement of the plane, always a bit worried – but when I’m flying one of these things I can just rest easy and even glide off for a snooze.”

Felix: “What, are you deadheading this flight?”

“Actually” Rob admits, “I’m on my way home to Australia. I run a school for commercial pilots in Melbourne.”

Felix: “That’s a good long flight. You have about eight hours more, from Jakarta, correct? I’m only on my way home to South Jakarta.”

The Australian perks up. “Oh really? You live in Indonesia long?”

Felix nods. “Three decades.”

The other man looks thoughtful. “Then perhaps you can explain something for me – about the Indonesian character. I’m rather puzzled.”

Felix: “About the pilots, you mean? I presume you have Indonesians as flight students. How are they?”

Rob: “Oh, they’re great students. Always on time, they don’t drink, polite and attentive. Some of our best students. But… something concerns me…”

Felix: “Shoot. Go right ahead.”

Rob thinks for a moment. “Well imagine you are sitting in the left seat of a thirty-million-dollar Airbus A-330 simulator.

“It’s totally realistic. You soon become convinced you are really flying, with the high-definition screens, the sounds of the engines and the fact that when you actuate the sidestick the whole thing tilts over to the left or right.”

“It’s sitting on stilts – hydraulic stilts, as I recall” Felix volunteers.

Rob: “Yes, that’s correct. Now here is how we train students for an emergency.

“Imagine you are sitting in the left seat. Everything is going perfectly; you’re moving along in level flight when all of a sudden you get a warning that you are losing hydraulic pressure to the rear control surfaces. The horizontal stabilizer.

“This is developing into a serious concern, distracting you from flying the plane, when you hear a buzz from the fire alarm in the left engine. Then it stops, and starts again; with such an intermittent alarm you cannot be sure whether it is a real or false reading.

“You confer with the co-pilot about the possibility of finding a place to land, quickly, just to be on the safe side. This is also an approved strategy in our training.”

Felix smiles. This is becoming interesting – but not for the flight crew. They are likely sweating. They do not want to fail the course out of ineptitude.

Rob the Instructor continues. “Now all this time you are monitoring your declining hydraulic pressure, thinking about a potential leak in the system, and having to bring it down because of a possible fire in an engine – “

Felix: “Yes, then what?”

Rob: “The radio comes on with a warning: ‘Air Qabur 666, you have a thunderstorm ahead of you. The last pilot to go through it reported numerous microbursts.’”

Rob smiles. And frowns. “This is where Indonesian pilots tend to freeze up. They panic and do nothing.”

Felix nods, knowingly. “Like… ‘deer in the headlights’?”

“Precisely. Just like a kangaroo caught in your headlights, when you’re barreling along at a hundred twenty an hour. They freeze up. And you may even plow into them.

“So, you’re the expert on Indonesian behavior. Why does this happen?”

Felix thinks back to a business conference several years previously. Bingung. The word with so many nuances in translation.

Felix: “We have faced this, with a senior executive who was arrested one day, right in his office, for corruption.

“Our staff panicked. They did not know how to handle the situation.

“So senior management hired an expert in ‘Cross-Cultural Communication’ to hold training sessions in our Jakarta and Medan offices. This guy was really good. According to him, conflicts in a professional, business or engineering environment can often be traced back to differences in culture.”

Rob: “How does that work for Indonesians?”

Felix: “Not just Indonesians – Asians in general do not like surprises.”

Rob: “Oh really?”

Felix: “Asian cultures are old – very old in many cases. Behavior and language are strictly defined and highly-stratified, so you know at any given moment how everyone around you fits in the social hierarchy, what you should do and what you should say. Such certainty makes society supportive and comfortable…”

“…if not very exciting!” Rob jokes. “Not at all like Australian society. Guy walks down the street with long hair and old clothes and you can’t tell if he’s a bum or a multi-millionaire.”

“That’s it” Felix nods. “It’s technically known as ‘Uncertainty Avoidance versus Uncertainty Tolerance’ and unless you’re traveling at 37,000 feet at 700 knots an hour it doesn’t matter so much – as long as you can make allowances for it. That’s what our training was for: learning to respond to an unexpected situation. A ‘black swan’ scenario.”

Rob the Australian Instructor smiles. “Like the Allied sub commanders during the Pacific War. They’d do crazy maneuvers and completely bewilder the enemy Japanese. Like sneaking up behind a Jap freighter and staying about 20 feet under its propeller so the enemy radar or sonar couldn’t locate it. And if the Japanese were to throw out depth charges they could sink their own vessel.”

He frowns thoughtfully.

The cabin is quiet, except for the dull placid roar of the four big engines pushing the A-380.

Rob: “Aircraft pretty much fly themselves these days… until they don’t. Somebody once described the commercial jet pilot’s job as ‘Weeks of boredom punctuated by moments of terror’ and that sounded about right to me.”

“Indonesian air safety leaves a lot to be desired,” Felix sighs. “And now Boeing makes it worse with airplanes that won’t let you stop them from committing suicide.”

Rob: nods sadly. “I used to hear ‘If it ain’t Boeing I ain’t going’. But I haven’t heard that one lately. They’re in deep trouble.”

Felix: “At first they were tending to shift the blame to the Indonesian flight crew.”

Rob: “Yep, when the pilot and co-pilot are dead the easiest thing is to put the crash down to ‘pilot error’. Who’s going to complain?”

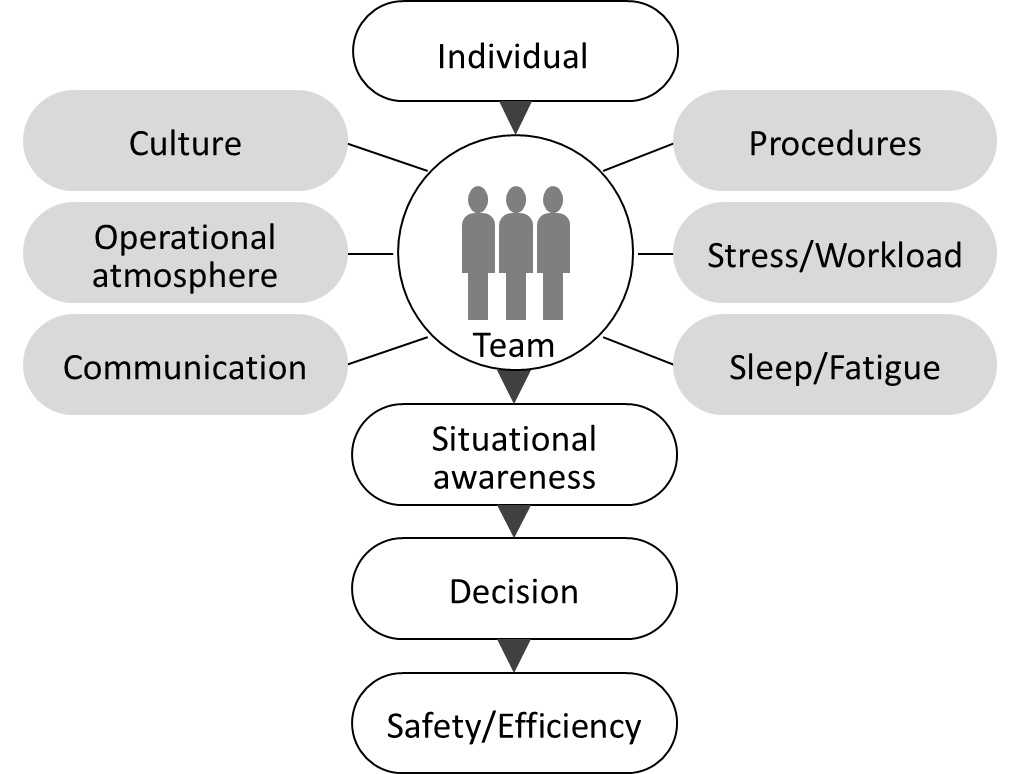

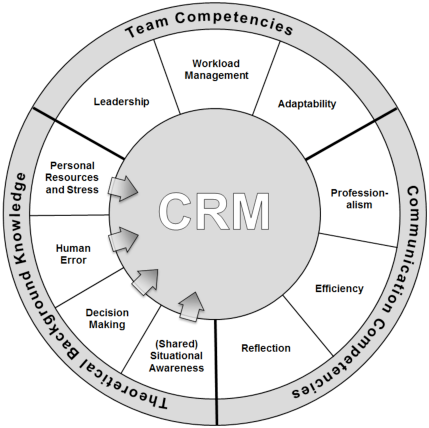

CRM

The Australian sits back and remembers. “Do you recall about five years ago when various airports around the world threatened to ban Korean Airlines from flying in their air space?”

Felix: “Yes, I do recall that. Wasn’t it because of all the crashes that they traced back to the pilots having a military background?”

Rob: “That’s right. And when the guy in the left seat is a big macho he-man jet jockey the other crew members will be reluctant to let him know he’s making a bad mistake.”

Now Felix remembers.

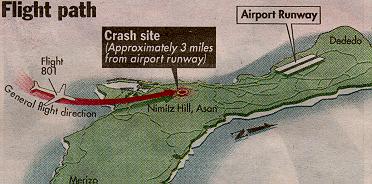

“Like that crash in Guam, where all the honeymooners died.”

Rob: “Correct. When they analyzed the data on the voice recorder they clearly heard other members on the flight deck discussing whether they shouldn’t tell the Captain the 747 was too low. But nobody had the courage to risk their job and confront the boss so they let the aircraft go smack into a hill short of the runway. And died.”

Felix: “How to get around that?”

Rob: “If you have an opportunity study ‘Crew Resource Management’ on the internet. There’s a detailed explanation on Wikipedia. Basically, it comes down to a ‘sterile cockpit’ where no small talk or conversation is allowed: the only communication has to do with flying the aircraft. Each of the crew members has his or her role defined precisely, and emergency procedures are defined as well. CRM has saved a lot of lives and rescued many aircraft in dangerous situations.

“So why does Indonesia have such a poor safety record, in your opinion?” Felix innocently asks the Australian aviation expert.

Rob: “Probably comes down in part to training. I heard a few years back that Garuda Indonesia was only paying their pilots around USD 3500 a month. To fly a two hundred million dollar airplane, with 400 or more people on board.”

Felix: “That’s about what a middle manager makes in Jakarta these days.”

Rob: “Also, maintenance. When an aircraft goes into the ground – or worse, the ocean – it’s not always possible to tell what brought it down. The Indonesian Air Force is still flying those old Hercules, for instance. Can’t be sure how they are being maintained.” He sighed. “We’ve been really lucky with Qantas.”

Felix recalls another tragedy. “Language problems in the cockpit, like the Air Asia Indonesia Flight 8501 crash, where the Captain was saying to the First Officer ‘Pull down with me!’”

The Australian snorted. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

Felix: “Whatever it meant they ended up in the drink. It seems the two pilots were applying opposing inputs to the controls – they simply canceled each other out, right through to the end of the black box recording. The Captain was Indonesian but the co-pilot was from a French territory – Martinique.

“As a professional do you think a western crew could have saved the aircraft?”

The Australian grimaced. “You can never tell. Maybe, maybe not. Air crashes are almost always the inevitable result of a number of little problems in a row that build up to a point where control of the aircraft is lost. This includes weather, getting confused about a situation or simply lost, not knowing where you are – like the Russian captain of the Sukhoi Superjet that smacked into a volcano – miscommunication or lack of communication, flight crew fatigue and simple crew error, which is what brought down Air France Flight 447, heading out from Brazil in a thunderstorm. If the Captain had not taken his required rest break it would probably never have ended up like that.”

Felix recalls reading something about flight software. “And today computers do most of the flying, even takeoffs and landings. What do you think about that?”

Rob: raises his hands. “Oh it’s great, particularly when you have a lot of planes stacked up to come in at Heathrow or a number waiting their turn to land at JFK. But it’s only great when it works. And now there is quite a bit of discussion in the industry about degraded hands-on flying skills, especially with the younger pilots who have never flown legacy aircraft – many not equipped with autopilots. For them it’s no different from a computer game. But of course it is when the computer goes on the blink.”

Felix grimaces, thinking of all the flying he is forced to do in his profession. “Your flying skills: use them or lose them.”

Rob: “That’s right. When the computer decides to do something stupid or crazy and you have to take over, you better be able to handle an unpredictable situation. There’s where experience actually flying the airplane manually comes in very handy.”

Felix: “Like landing in the Hudson River.”

Rob: “Like landing in the Hudson River.”